SWENSETH LAW

|

A comprehensive estate plan should include a Durable Power of Attorney, a Health Care Directive, and a blanket HIPAA release. HIPAA, the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 created the health information privacy requirements for providers of health care services. HIPAA's privacy rules prohibit health care providers from sharing patients' private health information with anyone whom the patient has not authorized to receive such information.

A Health Care Directive appoints an Agent, and often alternative agents, to make decisions for the Principal. The Principal is the person granting the decision-making powers to an Agent. The Agent appointed in the Health Care Directive is generally considered to be authorized to receive the principal's private health information when the Principal is deemed not able to handle his/her own affairs. That makes sense. We wouldn't want your Agent making decisions without knowing the Principal's health care situation. That would be dangerous. Some people believe that the Agent doesn't have the right to receive the Principal's private health information until the Principal cannot speak for himself/herself. What would happen if the Principal is unable to speak for himself/herself because of a car accident or for some other sudden reason? That Principal needs health care decisions made in an emergency. Of course, emergency medical providers will provide the medical care necessary to deal with the emergency, but if the Principal has some non-obvious medical condition that the emergency personnel need to know? If the agent has not been able to receive the Principal's health information, then no one might be able to warn the emergency personnel about the Principal's condition. Your Agent might not be available in an emergency situation because the emergency personnel will probably not be able to look for the Agent (or even a Health Care Directive) while trying to attend to the Principal's emergency. Health care professionals won't withhold emergency treatment while looking for the Agent. That said, in the aftermath of the emergency, medical providers will want permission from the Principal or the Agent to provide follow-up care. This follow-up care will not be "emergency," but it may be pressing. Because of whatever created the need for emergency care (like a fall, an accident, or a stroke, for example,) the Principal may not be able to make a decision or may not be able to communicate his/her decision on health care matters. As a result, the Agent may need to make these decisions and, in some circumstances, may need to make these health care decisions quickly. When time is of the essence in a health care setting, the Principal's care should not be put on hold while the Agent learns for the first time about the Principal's potentially complicated health conditions. Think ahead about the possibility of such an emergency. Would you prefer to create a broad HIPAA release to allow the sharing of health information to your Agent and the alternative agents named in the Health Care Directive? It may be important to include additional family members, or close friends, that might be involved with and assisting the Agent at the time the Principal needs care.

2 Comments

If you are married, and you or your spouse has been in the hospital and/or rehab and/or nursing home for more than 30 consecutive days, you may already be in a Medicaid spend-down for long term care coverage. And you don’t even realize it!

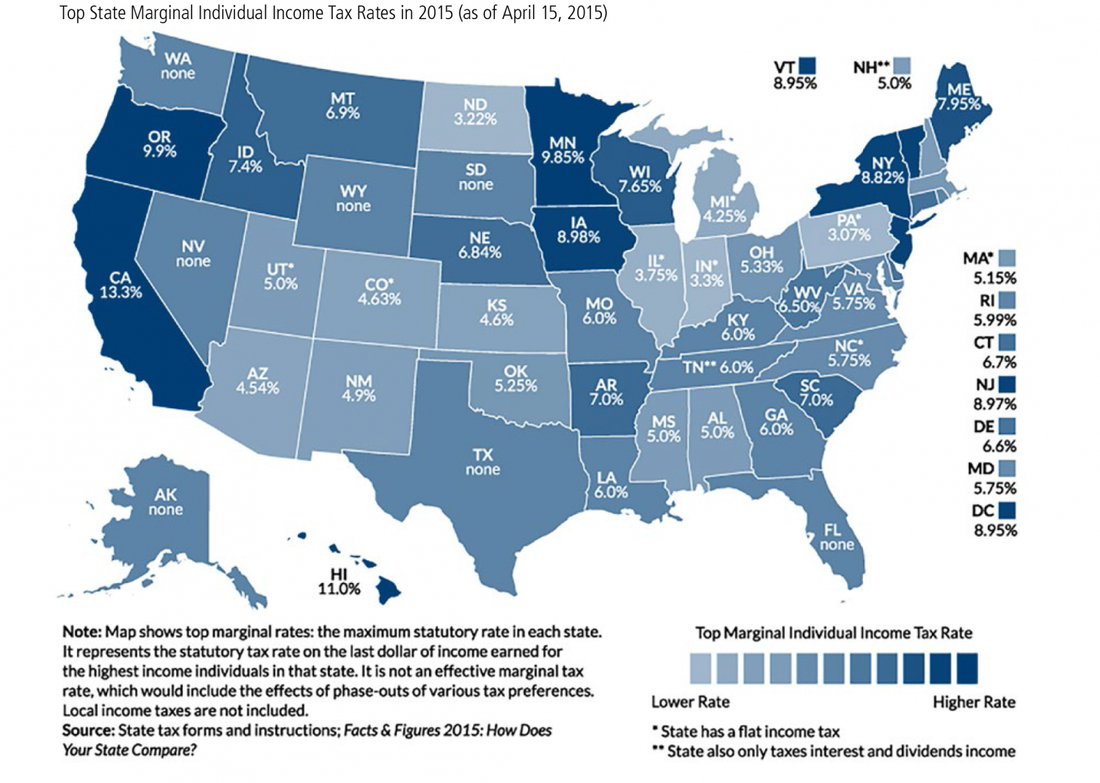

Let’s start with a discussion of the amount of savings or assets that the “well spouse” can keep when the “ill spouse” asks Medicaid to pay for his or her long term care. By savings or assets, I mean what is left at the end of the month after income is received and bills are paid. Medicaid labels savings and other assets as “resources.” The amount of resources that the “well spouse” can keep at the time the “ill spouse” gets Medicaid coverage is called the Community Spouse Resource Allowance, commonly abbreviated to CSRA. For most couples, the CSRA is half of the assets at the time the “ill spouse” had to move out of the house for medical reasons and stayed out of the house for 30 days or more. The first day of the month during which the “ill spouse” moved out is called the “snapshot date.” (That’s not the official terminology, but I like that term because it’s the most descriptive of what happens.) Please realize that, on the “snapshot date,” the “ill spouse” is almost always still at home and may not realize that, before the month is over, he or she will be out of the house for medical care and/or custodial care for an extended period of time. (The “ill spouse” is out of the house on the “snapshot date” only if the “ill spouse” becomes ill or gets injured on that first day of the month.) The “snapshot date” on the first day of the month seems illogical because, most of the time, nothing medical happens on that day. It’s logical only when you realize that Medicaid works in whole months. It’s just too difficult to break financial records down into individual days. If the couple had less than $47,688 on the “snapshot date,” the “well spouse” will be allowed to keep more than half of the resources because the “well spouse” is allowed to keep the first $23,844 of resources as the minimum CSRA. (Unfortunately, if the couple has less than $23,844, Medicaid will not give money to the “well spouse” to bring him or her up to the minimum.) If the couple has more than $238,440 in resources, the “well spouse” will not be able to keep a full half because the maximum CSRA is $119,220. Any resources above the “well spouse’s” $119,220 will be attributed to the “ill spouse.” Note: The minimum and maximum CSRA are adjusted each year for inflation (if there is inflation.) The Medicaid page at ProtectingSeniors.com is updated from time to time with these amounts and other related Medicaid eligibility figures. If the couple has between $47,688 and $238,440, the CSRA is half of the resources. Note: Some assets, most notably the couple’s home, are not counted in “resources.” So, after all that, the “ill spouse’s” resources at the time he or she asks Medicaid for help is the couple’s total resources above the CSRA (that the “well spouse” gets to keep) and the $1,500 that the “ill spouse” gets to keep (expected to become $2,000 in July 2016.) All of the couple’s resources above the CSRA plus $1,500 must be spent-down before Medicaid will cover the “ill spouse’s” expenses for long term care. So, why does all this minutia mean that someone might already be in a spend-down. It matters because the “snapshot date” isn’t tied to long term care. It’s tied only to the “ill spouse’s” absence from the home for medical reasons for at least 30 days. The “snapshot date” from an injury or illness earlier in life (but still during the marriage) may be useful to save assets if the “ill spouse” later needs long term care. I know, you’re still confused. That last paragraph didn’t help, did it? (Some people would describe that as a good lawyer’s answer: entirely correct but completely incomprehensible.) So, let’s tell this with a story. For the rest of this discussion, I’m going to give names to the “ill spouse” and the “well spouse” in hopes of keeping further confusion to a minimum. So, the “ill spouse” is going to be Ward, and the “well spouse” is going to be June. Ward dropped a cleaver (sorry, couldn’t resist) on his foot 10 year ago, on January 6. He needed surgery and several weeks of rehab. He returned home on February 5 . (As long as he was out for 30 days, additional days don’t matter for this discussion.) Let’s say that Ward and June had $100,000 in resources on January 1 ten years ago (the “snapshot date” for his foot injury.) Ward recovered and returned to work. He continued to make money, and their savings grew. So, now, 10 years later, Ward has a debilitating stroke. June can’t take care of him by herself and needs to move Ward into a nursing home. (By the way, this scenario also applies to home care and to assisted living.) June would like to apply for Medicaid to help pay for Ward’s care. At the time of Ward’s stroke, they have $200,000 in resources (on the first of the month.) Based on the $200,000 in current resources, Ward would have to spend-down $98,500 (the amount left after half of $200,000 is reserved for June and $1,500 is reserved for Ward) before Medicaid will pay for Ward’s care. BUT, Ward has already had a “snapshot date.” Ten years ago, he was out of the house for medical reasons for at least 30 days. At that time, he and June has $100,000 in countable resources. As a result, Ward needs to spend down only $48,500 to get Medicaid coverage to pay for his nursing home stay after the stroke. June was allowed to keep $150,000 rather than $100,000. BIG DIFFERENCE. Note: The “snapshot date” resulting from Ward’s cleaver accident applies only to Ward’s future need for long term care. If June, rather than Ward, has the stroke, the earlier “snapshot date” doesn’t apply. Now, if June had a significant illness or injury of her own that resulted in her own medical stay out of the house for at least 30 days at some point in the past, that would create her own snapshot date. So, if you’ve stuck with me during this 1,000 word shaggy dog story, here’s the payoff: If you know a couple (maybe you and your spouse) in which one of them has had a 30 day stay out of the house for medical reasons, the couple should preserve all of their financial records from that time. (For example, bank statements, investment statements, real estate values, IRA statements, life insurance cash values, and annuity statements.) Those records might be very valuable in case the same person needs long term care in the future. Boy, that installment was about as difficult to follow as War and Peace. Sorry about that. I couldn’t find a way to make it any simpler. For the original article, please visit Protecting Senior News  Taxes are a growing concern, particular high-net-worth individuals. A great deal of ink has been spilled recently discussing increased awareness of the federal taxes, but what about the state taxes that are paid over time. Each state maintains its own tax laws to collect income or estate (or inheritance) tax. These different laws may have a significant impact on a taxpayer’s decision to relocate during retirement. Saving state income tax dollars can help improve cash flow and spending power in a meaningful way during retirement. Saving state estate tax dollars also can help increase the legacy that someone can leave to their family. As the “baby boom” generation retires, wealth preservation discussions increasingly involve decisions to relocate to another state. A retiree may enjoy nicer weather or a change of scenery, but he or she may enjoy some beneficial tax savings as well. Income Taxes Income tax rates vary widely from state to state. Some do not tax income at all (such as Florida, Nevada, South Dakota, Texas, Washington and Wyoming). Other states have tax rates that approach or exceed 10 percent. Some municipalities within states even maintain additional, regional income taxes. Some states distinguish between taxing wage income as compared to investment income (such as New Hampshire and Tennessee). Still other states distinguish between taxing retirement income as compared to other income. Within the states that do not tax retirement income, some distinguish among social security benefits, public and private pensions benefits and retirement account distributions when determining exemptions and taxes. It’s a complicated patchwork of jurisdictions and rules, but the accompanying illustration can provide some more clarity. Estate Taxes Prior to June of 2001, most states collected estate taxes based on the federal state death tax credit. In other words, they would collect one dollar of estate tax for each dollar of credit allowed on a federal estate tax return. After June of 2001, Congress changed the estate tax laws significantly over time. These changes ultimately phased out the federal state death tax credit. As a result, the majority of states (29) no longer collect any estate or inheritance taxes. Other states (6), however, still maintain their own inheritance tax system. A couple (2) collect both estate and inheritance taxes. Still other states (13 plus Washington, DC) have “decoupled” from the estate tax system by recognizing a lower estate tax exemption amount than the one available for federal estate tax purposes. Even though a taxpayer may not be subject to the federal estate tax due to its higher exemption amount, that taxpayer may be subject to a state inheritance or estate tax in light of these changes. Some taxpayers consider changing residency during retirement in part to avoid these estate and inheritance taxes. Moving Away Speaking in the broadest terms, there are a couple of options that taxpayers consider when relocating during retirement. Some taxpayers sell their home and relocate to another state. Others purchase another home and share time between their primary and seasonal homes. The problem with the latter approach usually revolves around two concerns. First, states often define residency differently for tax purposes. Second, the state a taxpayer has left usually will miss those taxpayer dollars (and may still try to collect them if possible). Many states that are losing tax dollars have increased their audit practices, especially in cases where taxpayers retain some connection to their state. These states may not simply accept a round trip plane ticket to bookmark the dates a taxpayer claims to be absent from that state. They now may review a long list of facts and circumstances to demonstrate a taxpayer’s true intent to make a new home a permanent residence. Taxpayers must plan carefully when moving from one state to another while retaining more than one home. For this purpose, it’s not only important for a taxpayer to prove he or she has arrived in a new home state; it’s also important for that taxpayer to demonstrate a formal departure from the prior home state. This burden could prove difficult when the taxpayer maintains a home and other ties to the former state for family or social reasons. Failure to plan properly could result in paying more state income taxes than intended. This situation could arise not only because states collect taxes at different rates but also because states don’t necessarily offer credits for taxes paid to another state. In other words, income taxes could be due in more than one state. And, these costs could be surprising and significant. Original Source: Wealth Management According to the Alzheimer's Association, dementia “is a general term for a decline in a person’s mental ability which is severe enough to interfere with daily life.” Dementia is not a specific disease, but rather refers to a wide range of memory decline or thinking skills which impacts daily life. Millions of Americans have some form of dementia, and millions of more Americans will develop some form of dementia as our population continues to age. Different types of dementia may progress at different paces, which makes it important to consider the topic of estate planning fairly quickly for persons prone to or in the early stages of dementia. Being diagnosed with dementia or having a loved one diagnosed with dementia can be a scary, confusing time. Families dealing with dementia often have many questions. If you or a loved one are dealing dementia, perhaps you have considered the questions below. Or, if you have not, the questions below may give you some food for thought as you begin to approach the topic of estate planning in the context of dementia.

1. I am concerned I may develop dementia based on my family history. When should I start to think about estate planning? If dementia is a concern for you, the time to plan is now. Watching a loved one or family member struggle with dementia can be a significant factor in driving individuals to prepare estate plans. Most people caring for loved ones with dementia want to make sure that future generations do not have to deal with the pressure of preserving and protecting assets on top of struggling with the grief and/or emotional turmoil of watching a family member battle dementia. Planning early will ensure that your wishes are clearly laid out, and that you have adequate plans in place to alleviate stress on future generations. 2. My doctor has told me I have dementia. Is it too late to create an estate plan? Often times, dementia is progressive, and individuals in the early stages of most forms of dementia still have the ability to make important decisions. Receiving a “diagnosis” of dementia does not necessarily mean that it is too late to create an estate plan. However, it is important to act quickly to make sure that you have sufficient time to outline your wishes and create an estate plan to provide for your needs. The sooner the estate planning process is completed, it is more likely that you will be able to exercise the control you would like over your estate plan, and more planning options and techniques will generally be available to you. Once dementia progresses to the point where you are no longer able to understand the nature and effect of creating an estate plan, it will be too late to preserve your wishes and desires. However, until that point, you are able to, and should, implement an estate plan. Depending on the type of dementia and its stage of progression, it may make sense to have a medical opinion outlining the ability to make estate planning decisions. 3. How does a person get appointed to act for me when my dementia progresses to the point I am no longer able to act for myself? If you have prepared an estate plan, the terms of the estate plan will outline how someone takes over for you. Most times, this transition can happen without probate court involvement. If you have not prepared an estate plan, it is likely that a family member or other interested person will seek to have a Guardian and/or Conservator appointed by the probate court to act on your behalf. In Michigan, Guardians are appointed for incapacitated persons to make decisions on the living arrangements, medical care, among other things, for the incapacitated person. Conservators are appointed to act as the financial and legal representatives of incapacitated persons. Both Guardians and Conservators are appointed by the probate court and both have ongoing reporting requirements to both the court and the family members or other persons interested in the well-being of the incapacitated person. 4. If I am concerned about dementia, what are the advantages of using a trust? The use of a trust may make sense for individuals facing dementia. However, as with all trusts, it is important to properly transfer all assets to the trust to avoid the necessity of probate, both during lifetime and at death. Your trust will likely contain a detailed plan for determining your incapacity and a detailed plan for use of the trust’s assets for your benefit during incapacity. Trusts maintain privacy and allow for greater flexibility in planning. If you are considering the use of a trust, you should seek both legal and tax advice to make sure your objectives are being met. 5. I don’t have long-term care insurance. How do I protect and preserve assets in light of increasing cost for long-term medical care? Planning to receive Medicaid benefits can be a difficult task. Medicaid eligibility follows strict guidelines, both in terms of the amount of assets you own and the amount of income you receive. Additionally, if you receive Medicaid benefits, the State of Michigan can attempt to recover for benefits paid on your behalf through the Medicaid estate recovery program. If you are likely to need Medicaid benefits in order to provide for your long-term care, you should seek legal advice to learn more about the qualification and reporting requirements associated with these benefits. 6. I own a business with other individuals. How will dementia affect my ownership of the business? Often, bylaws or operating agreements associated with a business outline how the business owners’ interests will be passed upon death or disability. Business owners should carefully review these provisions to ensure that they are fair and understood by all other owners. In the event changes need to be made, it is important to make those changes as soon as possible. Absent a provision in the business’ governing documents, the business interest may end up being managed by a person appointed under a Durable Power of Attorney or by a court-appointed Conservator, as the case may be. Often times, the remaining business owners are not comfortable with having a “new partner,” which can cause tension. Therefore, it is vitally important for the business documents to properly outline the agreements of the business owners. Original source: http://www.shrr.com/estate-planning-and-dementia-answers-to-common-questions Initiating a conversation regarding estate planning can be difficult. Make it easier with these tips courtesy of NDSU Extension. https://www.ag.ndsu.edu/pubs/yf/famsci/fs1684.pdf |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed